WALRUS DISGRACE (an excerpt) Kellie Wells

TONIGHT I, Wallis Grace Armstrong, Kansas Amazon, am dusting off my two left feet and knock-about knees and am going for my fourth ballroom dance lesson at the Arthur Murray studio in Kingdom Come, a gift from my parents, who had high hopes for the steering power of a middle name and who try not to be disappointed that I've instead lived up all too readily to the stout stamp of the surname. You can imagine what a rich source of heckling being saddled with such a nom de guerre has been: Wall-ass Strong Arm, Wall-eyed Goose, Wall is gross, Walrus graze, et cetera. My mother, trying to assure me of a glamorous life of class-busting romance and help me elbow my way into abdicated aristocracy (such royal ambitions are hard to scare up here on the Great American Plains, but a girl can dream), named me after Wallis Simpson—the twice-married socialite who so captivated Edward VIII, Duke of Windsor, he abandoned his royal heritage and lived with her in exile. She dreamt up this hopeful handle not realizing the eighteen-pound baby she secretly believed had to be quadruplets, the baby stretching her belly beyond a reasonable arc, would, with this masculine moniker, be more likely to call to mind a steam shovel operator than a duchess, even one once removed (I can only assume my mother was and remains unaware that the Duchess fatale was an intersexual Nazi sympathizer).

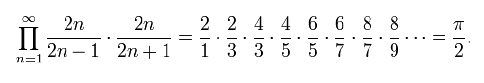

Would that I had been named rather for that developer of infinitesimal calculus, John Wallis, who gave us this: ∞. My mother does not know there is a man named Wallis who contributed to infinity, lent a shape to perpetuity, who formulated Pi. She would be perfectly appalled at the notion. She does not care for unending things. I have turned out to be a towering obelisk of a daughter, and the vastitude of me she finds sheer insubordination—Stop it at once! she sometimes shrieks into the blue air, stomping her strappy sandal and clenching her fists. She takes each aggravating inch personally. Sometimes on applications, questionnaires, medical histories, census forms, I sign my name thusly:

And I know it's my turn when the clerk, the nurse, the functionary purses her lips and sighs with fatigue.

After a trying day of looming, I found my nerves were ajangle, and I called Mr. Mundrawala, my instructor, to cancel, but he sounded disappointed and urged me to reconsider, insisting that "continuity and repetition are key to mastering the foxtrot. Practice makes graceful, Miss Armstrong," so I decided to go. Inexplicably, Mr. Mundrawala, not a hair over 5' 7", had decided it was best if he personally partnered himself with me, even though there was, by mortal standards, one reasonably tall man in the class, who was strangely prone to wearing elevator shoes, which meant his eyes could at least glimpse my clavicle if he stretched and I sagged forward. Mr. Mundrawala assured me that dancing with pint-sized men would be instructive, would teach me to move more thoughtfully through the world, help attune me to the feet bustling around me that I always have to be careful not to flatten.

"It's very nice to see you here, Miss Armstrong," Mr. Mundrawala said with a nod of the head, grinning broadly.

"Nice to see you too, Mr. Mundrawala."

"Please, you have now had the benefit of my instruction for how many lessons, three? As we are partners, it is time we observe the American custom of quick familiarity and employ first names, don't you agree? Yes, please, you may call me Mateen." He held out a delicate hand.

"Wallis," I said, and shook his paw, though it was, from his end, really more of a firm squeeze of a few fingers. He had the nimble grip of a flautist.

"A lovely appellation," he said sincerely. The first time I'd heard that from someone to whom I was not related.

There were three other couples present, all decked in ballroom duds, waiting to begin the beguine. I was wearing a black t-shirt, parachute pants (in case I ever figured out how to bail out of this body), and built-to-order sneakers, and, like every week, the others stole glances and shifted nervously, tried not to stare, thanked God for their small feet and wasp waists.

IN TENTH grade, Jojo Fridel asked me to the homecoming dance. Jojo was a gymnast, 5' 1" in platform shoes. I'd kneel down so he could mount the howdah of my shoulders, and he'd ride aloft, waving to the minions below, then he'd backflip to the floor, applause, applause. We were a novelty act and mostly well-liked, if at a long arm's remove, by the perfectly-proportioned and popular teenagers that haunt school dances (though not by the orthodontic wall-huggers, who felt they could ill afford to claim us). There but for the grace of God, I could hear them thinking as we jigged across the gym floor to the fervid caterwauling of "Ballroom Blitz." Most Aberrations of Nature know enough to dodge school gatherings and extracurricular activities of all kinds, but I felt a certain purposefulness in reassuring these young apple-cheeked, corn-fed American citizens of their good fortune in belonging to the First World. Jojo and I, noble savages, served as sort of an anthropological warning, a trip to deepest, darkest Africa for these middle class milk-faced Kansans, scrubbed mugs bland as pancakes, who were grateful for their V-8 Firebirds and split level homes with double convection ovens their parents' comfortable incomes provided them, grateful for statistically average IQs and bodies that didn't call attention to themselves. We were a mystery they hoped never to get to the bottom of, a hostile continent they liked knowing was out there—a place of corrupt heat, a constant cloud of mosquitoes, and unimaginable, fevered misfortune—but never wanted to step foot on. Just sharing a locker or lunch table with us, observing us in the natural habitat of our bodies, was safari enough for them. There was, of course, a committee of toughs who'd menace the likes of Jojo and me at any opportunity.

We were beat after an evening of performing to golden hits of eras so bygone we had no nostalgic claim to them, and had decided to cut out early, to leave the crepe streamers and ice machine fog to the couples who tottered like penguins as they stiffly slow-danced. The Kingdom Come High hooligans weren't the type to frequent sock hops—wouldn't be caught dead inside the gym while the mirrored ball still spun—but they were so incensed by the bald chutzpah of our showing our freak-of-nature faces at a school event they made an exception and waited in the parking lot for us (if mastodons and their trained fleas began to roam the earth freely, without even being hectored, where would that leave them? Equality, as any pariah knows, only causes to crumble the fragile social foundation on which both thuggery and outlaw glamour depend). There were four of them, Bobby Ehlers, Gary Schwartz, Heather Leatherwood, and Lucky Teeter, Bobby swinging nunchucks with calculated bluster and trying not to look pained when they hit him in the chest or back. Heather and Gary were clearly hopped up on something as they shifted from foot to foot and sniffed, their black eyes all spreading pupil. Lucky stood by calmly, hands stuffed in his dirty jeans' pockets.

"Well, if it ain't Mutt and…Mutt," said Bobby, which was their cue to swarm. I swung Jojo, fearless mahout, onto my shoulders and beat it down the gravel drive. They gave chase and began to pelt us with stones. I felt the nunchucks hit my back, then Jojo yelped and fell limp. I stopped, pulled him around into my arms, saw that the back of his head was bleeding, then felt a flak of gravel hit my legs, heard their hyena cackling. His eyes were open but dull, like smudged glass. He groaned groggily. I gently lowered Jojo to the ground and turned to face our four assailants. They were wild-eyed and rocking, bent at the knees, as though preparing to play a riotous game of tennis. Jojo was just a preliminary skirmish—it was me they sought to conquer. I imagined them knocking me out and battening me down like a ship they wanted to set sail on, securing me to the ground with string and thumbtacks I'd break free of with a shrug, those rotten Lilliputians, then I'd send them sailing alright.

Bobby Ehlers was fluttering his hands, motioning me toward him. "Come on, T-freakin'-Rex," he said then licked his lips, "come on, come on."

"Time to kick some Leviathan ass," said Lucky quietly.

"Some what?" said Gary.

"Shut up, dumbass," Heather said, pushing him aside.

"Cut it out, bitch!" Gary said, grabbing her by her black-rooted, corn-colored hair that had been scorched into brittle waves with a crimping iron.

I walked up to Gary and seized him by the throat, lifted him in the air, thumb on his windpipe. He began to gag and kick. The others closed a tentative circle around me. I pressed harder, and Gary's gagging thinned, his eyes bugged. They stopped and took a step back. I said, "Toss me your wallets then take off your clothes."

"What?!" cried Bobby Ehlers.

"Do it, and do it quickly, or Gary Schwartz becomes the next Kingdom Come High statistic," I said. "Too many drugs and thug friends always spoiling for a fight, just another misunderstood teen casualty from a broken home, saddest story you ever heard." I stared at Lucky, who held my gaze. Bobby took a step in my direction, and I dug my thumb into Gary's windpipe. His face was red as a setting sun and he gurgled. We all stood frozen, and I was beginning to worry they might be willing to sacrifice Gary in the name of the greater good of their black-hearted ambitions.

Lucky unchained his wallet and tossed it to my feet. "Do it!" he yelled. Jojo was now sitting up, rubbing his head. The others tossed me their wallets and began to undress. Jojo stood up and wiped his bloodied hand on his pants. Gary's jerking slowed.

Trying to slouch indifferently inside their gooseflesh, hands casually draped over shriveled privates and pubic hair, they briefly tugged at my heart, but I was committed to this showdown now, my hand glued to Gary's throat. Jojo gathered their clothes and wallets and handed them to me. "Let him go," he whispered. I dropped Gary to the ground and he gagged and gulped, reached in the air with a splayed hand. Jojo picked up a rock and chalked a circle around his body, and we backed away. "You're fucking dead meat, man!" Bobby shrieked.

As we left them, I saw Heather kneeling by Gary, who held his throat and backhanded her in the face. "Dead!" Bobby screamed after us.

When we got to the end of the drive, we tossed the clothes and wallets into the stagnant pond. Heather's shirt caught on a cattail, everything else sank into the green murk.

There are times when anger wells up inside of me like a geyser aboil, and when it blows, I make the person in front of me pay for the infractions I've let slide. But honestly, I'm not a violent person by nature. My brother used to say it was just my Old Testament temper erupting. Once allowed to rise up, it's hard to tame a diluvian dander.

Tonight at the dance studio, there was a man, one of the eager-to-trot jackanapes, the trotting fox trying hardest not to stare, who looked a lot like Lucky Teeter though with a considerably thinned mop and a more weasly snout than I recalled, Kingdom Come High's own Roister Furioso all grown up, though I would sooner expect to see Lucky Teeter asprawl in a gutter than cutting a ballroom rug decked out in souped-up duds. I caught his eye and he nodded once before he stepped on the foot of his partner, who squawked at such a pitch we all froze mid-shuffle. Lucky Lookalike pulled a toothpick from his pocket, popped it between his gnashers, and folded his arms while his partner shook her shoe at him and defended the honor of a wounded bunion. Mr. Mundrawala looked up at me apologetically, though I, Walrus Disgrace, body stalled inside a maneuver I was about to botch anyway, I was pleased for once not to be the main attraction.

The Inoculation of Mateen Mundrawala

THE NEXT WEEK in class, Mr. Mundrawala was awol and in his place was a buoyant redhead wearing a cinched dress whose skirt billowed showily when she whirled, which she did randomly while chattering. She glided and pirouetted whoosh-whoosh across the dance floor and clapped her hands twice when she reached the other side. "All right, class," she sang, "partner up. Tonight we're going to learn the thrilling steps of…the tango!" She threw her hands into the air and grinned in a way that made my jaws ache.

"Olé," said a low voice beside me, Lucky Teeter's dancing doppelgänger. "I hear it takes two," he said and held up his hands unsteadily, as though he were trying to catch a giant baby thrown from a burning building, and then he smiled and revealed a front tooth capped in silver.

"Where is Mr. Mundrawala?" I asked, and he wouldn't drop his paws, so I reached down and clasped his reaching hands in mine.

"Search me," said the man, and he shrugged his shoulders. I resisted the urge to pull him up into the air and dangle him by his arms until he produced some useful information. He smirked belatedly and raised his eyebrows, and if I'd had some electrical tape on hand, I would have slapped it on his forehead and stripped his prominent brow bald. I gave a windy sigh like a furnace churning into action, dudgeon aswell, in no mood to gambol with a high school ruffian turned weekend rug-cutter. Bullies, like giants, do not improve with age.

"I ain't lucky," he said, and I thought he offered this as explanation for why he was willing to tango with a woman who was halfway to heaven, a woman he could look in the eye only by way of catapult or trampoline.

"Yeah, well, clearly good fortune frowns and flees to the nearest exit whenever I enter the room," I parried. I suddenly felt like an out-of-work pugilist long spoiling for a prize fracas and thought my fist might just fly forward unprompted and pop him in the beak.

"Lucky Teeter? I ain't him. I'm his older brother Leon."

I looked at that glinting tooth and had the vaguest recollection of Lucky getting into a souped-up Chevelle one afternoon after being suspended for scrapping in the hall between classes, pummeling some pimpled freshman in need of initiation. Leon took his right hand from my left and lifted it in the air as though he were trying to entice a bird from a limb then grabbed my hand and shook it mid-flight, howdy-do, howdy-do, shake-shake-shake.

"You're Leon…Teeter?" I asked, relaxing my arm, lowering the altitude of the handshake.

"In the flesh. And you're Wallis Armstrong, am I right? Lucky always had it in for you." Lucky, that is Leon nodded his head that was balding in a way I suddenly found touching, a pink skullcap, a slice of grapefruit, a plot of recent desert encroaching on a forest struggling to remain lush.

"He mentioned me?"

"Your ears must've been on fire a lot when you were a kid. I bet you come up as a topic of conversation often enough to keep your bean toasty in any season." Leon smiled again and that tooth made me think of the disco ball revolving above us, scattering doubloons across the floor.

I felt suddenly enervated in a way only people over 8' can feel.

"I'm just ribbing you," he said and he chucked me on the arm. "Like I said, I ain't Lucky. I sell insurance." He raised those eyebrows again. "Lucky had a sore spot for you because you had what he always wanted. He just wanted to be big, you know? Big shot. And you were a girl, so that didn't sit well with him neither. Lucky's like our dad in that way, old school. They like their gals barefoot, mouths zipped, and out of sight except to deliver a Schlitz as they watch the game with the boys."

"And you're not Lucky you keep telling me. So what saved you from this fate, Unlucky Teeter?"

"My sister." Leon let his gaze fall to the floor. One advantage to having a head perched above everyone's sight line is that necks quickly begin to ache when heads are angled upward and this cuts potential gabfests short. I stole a longer look at Leon while I had the chance. His body was no surprise, neither slight nor portly, but his face was long and thin, an older, slowly thawing version of Lucky's. His nose was so dominant that the rest of his face appeared to be retreating to safe ground so as not to be indentured, but his throat was drawn and his eyes bulged, as though he'd gone on a diet from the neck up.

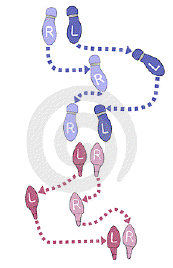

"What, having a sister taught you to pretend that girls are human beings too?" While Leon and I were having this conversation, the rest of the class was tangoing wildly around us, as though they'd been kept in a dank cell beforehand, denied movement, and were suddenly released onto the dance floor. They thrust themselves together cheek to cheek, bent slightly at the knee, arms thrown out in front of them, looking like mirrored guerrillas advancing with bayonets, their embattled homeland in need of fierce defending. The teacher's mouth was hitched up at the side disapprovingly and she stared at Leon and me, trying to stink-eye us into hoofing with the rest.

"You ever hear of precocious puberty?" Leon asked, his silver tooth hidden behind his lip as he spoke. I imagined tiny dancers twirling beneath it. This question smelled like a gag cigar just waiting to explode in my face, so I said nothing.

"Our sister Maddy, she got the, uh, you know, the red curse when she was six years old."

"What, the measles?" I said and sniffed. Where, where was Mr. Mundrawala? Why was I standing amidst couples prancing with stiff lockstep resolve, talking to Lucky Teeter's older brother?

"The doctor told us she was going through precocious puberty and that her body was speeding up. She was turning thirteen seven years ahead of schedule." Leon looked at the teacher and then back up to me. His forehead was creased, a rumpled blanket. "She had fits, these seizures like, sometimes dozens a day. She was always the sweetest kid and then she'd just start screaming herself blue for no reason. She was still small, the size she was supposed to be, still had those red cheeks and baby fat, but inside her body was racing, dragging her out of her childhood and into old age. They couldn't do nothing about it." Leon rubbed the pillowed skin below his eyes.

"My folks home-schooled her and we pretended everything was hunky-doodle, like that sad-eyed tiny lady who sat at the table clutching her stuffed duck was some half-cocked homeless relative we took pity on and invited to supper every night. Maddy was tired all the time, slow-moving. Aging at breakneck speed takes a lot out of a body. We were watching her die and acting like we weren't. It was like one of those movies where the flower sprouts from the ground, shoots up into the air, grows leaves and petals, and opens into a quick bloom, all the time clouds are zooming by in the background, the sun up, down, up, down, like it's doing calisthenics, then the flower starts to droop and drops its petals and withers down to a stalk of nothing in a matter of seconds." As Leon spoke, he fixed his eyes on the dance teacher, her whirling skirt. "It was like that with Maddy." After he finished this speech, he had that slightly shriveled look about him that suggested his heart had cracked in the casting and would forever leak, the heart of a boy who had loved an accelerated girl.

Then he lifted his arms up in the air again, said, "You lead," and I bent down at a nearly ninety degree angle to press my cheek to his, my caboose shoved out into the fast lane, and we parted the other tangoers as we charged across the floor. I felt Leon Teeter's cracked heart thump through his shirt against mine.

And then I thought about Lucky, thought about him trying to steal a kiss from Heather Leatherwood, who would have turned her head to the side, because Lucky was not attractive, despite a certain seething charisma, and she was the sort of girl who, angry about those disadvantages over which she had little control, would demand a dimpled chin at the very least. I thought about Lucky sitting at the stagnant pond, rolling a cigarette, then, out of boredom, pressing the cherry into his forearm. I thought about him sitting at the dinner table with his sad time-lapse sister, trying not to notice as she rocketed through her childhood beside him. I remembered a newspaper article I'd read about all the meth labs blowing up one by one in Hope, Kansas, and I thought about how a name can doom a person in a world just waiting to thump you on the chest and show you what hubris it can be just to wake up. The universe is a bully with nothing better to do. Leon's cheek was moist and warm and soft as a baked apple against mine, and I felt just then regretful that I hadn't slipped out the back that night, that I'd made Lucky Teeter drop his trousers, had contributed to the further souring of these curdled lives and their unseen sadnesses. Inch for inch, I thought, the lumbering have more amends to make than others.