FAMILY PORTRAIT Jess Stoner

My mother asks each of us to wear a white shirt for our family portrait. I’ve never liked when you can see the bra beneath. I always want to look. I‘ve never liked how much I don’t want to look after I’ve looked.

No one wants to do this today. Or maybe my parents are embarrassed because they do, or maybe their unease is un-gilded. Regardless, we decide we will not stand on the stairs in chronological order. I once heard a Christmas-morning story about parents who demanded their grown children sing “O Tannenbaum” while they descended in reverse order of birth towards their presents. There is probably photographic evidence of them having to do this, which somehow makes it seem more horrible. Can they hear their song when they see the photograph? If we received this family’s “Season’s Greetings” portrait, in a card signed inattentively, would we see their un-caffeinated voices, hear notes tinny with antipathy and guilt? Their mother hopefully hears something very different when she finds the photograph in a drawer. Why I hope for a mother I have never met I do not know.

I borrow a pair of my sister’s pants for the photograph, as if preparing an image of myself I would never recognize anyway. I have never owned a pair of red capris. I would never wear white shirts that require beige bras so what I do not want to be seen will not be seen. The four of us are hardly ever this close to each other.

Photographs of people in deliberate poses are supposed to reveal their secret selves . When directed, each of us smiles in a way we never would if we started to laugh when someone with a camera was not near. In our portrait, I am thinking about how my upper lip curls and that there is nothing symmetrically pretty in me. I can see myself thinking this, when I look at the portrait years later, when I wonder if our secret selves are as strained as we appear. The woman who takes our picture is a friend from my parents’ church; she tells us to be ourselves. She does not understand that acting lifelike leads to a likeness farther away from being alive.

Taking the photograph of a person posed–deliberate, inauthentic–does not reveal the secret self. It reveals the secret wishes of the people who look at them. What does my mother think when she sees our portrait framed above the mantle, centred at eye-level? Is it, in its reverential place, a successful symbol of what it means to share a last name? Why did you take a shower so late? It does not matter if your hair is wet. I would’ve ironed that for you if you’d asked. Could someone vacuum the cat hair off the carpet on the stairs? I’m embarrassed of my husband. These are the things I think she thinks when she looks at it now. What she sees I cannot know.

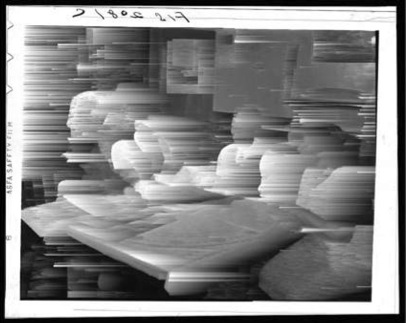

The family in this photograph seems to like each other in a way I have been trained to believe is false. The woman on the left with her hands on the table would never have her hands on the table like that. Her wedding ring looks so much younger than she is. A chair blocks the door. Do they know they are trapped?

What headline are they laughing at together? On January 20th in the year this picture was taken , 1942, the Germans announced their plans for the “Final Solution.” I like that the little girl reads the comics, even though she’ll see no little girls in the comics she reads. When I get drunk I always talk about how Nixon was afraid of Doonesbury. I have never found evidence of this. Yet I have told people on multiple continents this something that may not be true. They will blame me when someone makes them feel stupid about its untruthfulness.

The women wear their aprons so tidily; it is evident they have done no cooking. Has the photographer asked them to prepare themselves so that when other people see their portrait they will not be confused for the family of immigrant fishermen they really are? Their bodies are hidden in a suggested lie. At least three of them show no indication of having feet. We think there are two mothers in this photograph because they look like they are listening. Does anyone read the paper so neatly? It creases and folds in incorrect ways that make holding it feel uncomfortable, make you feel like the image of someone reading a newspaper, and then you have to unfold and then make the crease perfect again and it takes longer to do this than to read the article, which started on the page before, yet you cannot remember where it left off, and now it is going to take too long to re-crease and unfold and re-crease and anyway anyone could probably tell you how it will end: nothing is ever truly terrible when you are rich.

I am a daughter. The woman who must be the mother of the child in that photograph defined herself first as a daughter. She was a daughter before she realized she was a person. I am lying when I say I can recognize myself in photographs. I have never known who I was because I first defined myself in relation to someone else.

I rarely wonder what my father thinks when he looks at our portrait. It is not that his thoughts are opaque. It is that I have always been afraid to know them. Where is the foreground? The father, who is more son than father in this photograph? Or is it the table? I want to tug on its vinyl-coated crochet, which I’m convinced is taped down. I wonder what the table looks like underneath, if the way the covering is taped is ugly and would betray the entire family if anyone were to ever see it: under the table where the father wipes what he’s plucked from his nose, the morning after he has had too many pints, when he disrespectfully reflects at the table that what he’s plucked looks like an unpronounceable Eastern European country, or because that’s where their brat of a daughter hides when she’s fed the cat ketchup.

In our family portrait, our hands on the railing is what I see. I never paint my nails. In the photograph, the polish on them is chipped. This is my sister’s fault; when I come home and see her we have an unannounced competition to prove who’s more feminine. I paint my nails because I have given up. Our fingers look like props we’ve put on. There is something so overcast about how useless they look. If it was raining outside that day my wrists would’ve ached. The wrist in a portrait never aches but only indicates where the arm connected to it, hidden underneath the shirt, should be. In preparing the image of myself in this portrait I forgot some things. I do not own nail polish because I do not own pantyhose. Every woman who owns pantyhose owns nail polish to keep them from runs. Fingers are so unlike breasts, which shouldn’t bother me as much as they do. Once I wondered what my sister’s nipples looked like. Not everything has to have consequence. Nothing has to be idealized to be made beautiful. The railing that our hands rest on, some of us gripping tighter than others, could be the thing that becomes beautiful. It could be a metaphor. The railing could not stop me from falling drunk down the stairs and landing on the landing. The railing is to code , however, which my father proudly pointed out once to an ex-lover of mine who was perpetually unemployed.

Why do I feel a guttural sadness when I look at a photograph of people who knew when they posed for the photograph that all who saw it would know they were posing?

Is there some confidential transcript of history translated in the way each of us appears? My father, smiling as if this is what a smile looks like. My sister, resembling the perfect likeness of get this over with, and then myself. I am the only one not lying because I look genuinely happy in the picture . I do not look crippled by anything. Even my hand on the railing is there softly. As if I naturally turn towards that direction when I walk up the stairs. No one should not look at our family portrait because no one will see the summer breaks before it was taken, when I would come home drunk as hell, having just thrown up in the neighbors’ hedge, crawling through the window my father had cracked open on the enclosed front porch because he knew I would not have my key. You will not see that when he woke up and saw that I had dragged backyard furniture to the bushes in the front yard so I could scrape gracelessly through the window, he never complained about having to move things back where they belonged. We get our photographs taken as if to argue the fact that we are worth looking at. Experience us. Experience the shit out of what it means to be in our family when you look at our portrait .

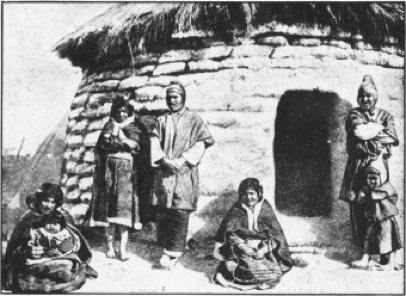

This photograph’s caption reads: “THE CHEERLESS HOMESTEAD OF THE ANDINE INDIAN.” We are told to witness “the miserable domestic conditions.”

Baudelaire said: “It is useless and tedious to represent what exists, because nothing that exists satisfies me…I prefer the monsters of my fantasy to what is positively trivial.” When I first read that sentence, I read “family” instead of “fantasy”: “I prefer the monsters of my family.” In doing so I made them un-trivial, even if I would prefer them that way. We are all smiling in our own way. Only my mother and father at this point know that she aborted their first conceived, never born. This family in our family portrait does not exist. Some years after this photograph, my sister will tell my mother she is a lesbian. Who knows if my father regrets the porn in the computer’s cache, which he does not know how to clear, that shows his devoted interest in relationships between women, an interest in concert with my sister’s. Or nothing like my sister’s. We do not talk about her preference for sexual accoutrements. If she has them. Or whether she likes certain girls better.

To describe a photograph is to lie. When my mother takes the portrait off the wall to re-paint the room in a different shade of brown, she says, “We took that when Molly came home for the holidays. She hadn’t been home in months. The four of us hadn’t had a proper picture taken in decades.” This is her verbal caption. It is meant to rationalize the photograph that froze an infinitesimal moment in a past that is no longer. Even if she had said, “The four of us took this photograph in December,” it still would’ve been a lie. We didn’t take it. We had it taken. Everything in it is passive. Everything is the same now as it was in the photograph. Preserved in something so misplaced we can only describe it as hope.

I cannot remember if the photographer told us to smile. We have been culturally trained and each of us knows to smile without being told. I smile a certain way in photographs because I think it will not show a double chin. I’m thinking, “I hope I do not have a double chin,” in every single photograph of myself that’s ever been taken since I was a certain age. The photographer probably said, “Smile.” Although we were probably already smiling when she said that. We were not caught with our sincerity down.

I cannot remember the names of everyone I have fucked. What would have happened if I had said that just before the photographer had taken the picture? Every female in my family laughs when they’re uncomfortable. That would have happened. The three females would have been laughing. We would’ve been caught with our sincerity down. Yet we would have been smiling in exactly the same way as we are in the photograph. I do not know how my father would have reacted. He does not exist in the hypothetical. Or the present. He exists in the center of a photograph. That debilitating space. The viewer’s eyes want to be encouraged to move from there. To experience an image in more than a moment. To experience one moment in more than one moment. The debilitating space in the photograph strives to keep us from this experience.

All the women wear short sleeves in that Sunday morning family portrait. They are all on the outskirts. That must be the father in the middle. Every father is in the dead landscape of a photograph. Every time I see a father, I feel not a pain in my diaphragm but something that makes it contract, so that the way I breathe becomes not an unconscious, mechanical response, but a kind of chronic exhaustion when I think about how many more breaths I will have to take. I pay attention to how this feels so that the paying attention takes the place of whatever it is I am actually thinking. There is not space for both. The women wear flowers like the wall does. The textures of their social roles compete with what’s knotted on and in the men. Is the daughter who is now a wife thinking, “Our arms are touching and I do not even know who you are?” Is the little girl’s mother thinking, “When was the last time we fucked?” as she looks over her husband’s shoulder. She likes to think those thoughts in front of his mother.

Here is the photograph of my family which once hung over the mantle:

Can you tell what’s been cropped out? The recycling near the door that she asked us to take out before the photographer arrived, and we didn’t, because when we are with each other we are gripped by a violent malaise and there is the cardboard from a frozen pizza that had green peppers when she knows I do not eat green peppers, rolls of toilet paper rolls with bits still to be plucked, eleven Bud Light cans which had been in the fridge for almost a year when I arrived and drank them sour the night before, the mashed-potatoes crusted on the microwave bowl that comes with the box, who has the time to mash from scratch anymore, the tin-foil that if we were more conscientious we would’ve washed and then used again. If I tell my parents that I have given serious thought to civil war re-enacting, learning French, attending medical school, faking my own death, getting into derivatives, becoming an English teacher, moving to Vancouver, taking the LSAT, studying C++, going into advertising, whatever that means, this would all be better than the truth. Sometimes I wonder if I’m the only person who wonders if Star Trek: The Next Generation was actually set in the past, because we are in a different time than we think. Or how come no one worries about syphilis anymore? There is a Law & Order: Special Victims Unit episode where four people are killed by the guy with the mole on his face who was in another TV show that was on before I was born; it turns out his brain is melting from syphilis because his life insurance company never told him he had it.

How do you take a photograph of that? Where is the divinely gifted creator of images who could capture that in an instant? Where is the photograph that goes into the literate projector? That instrument I am secretly building in the basement that translates image into text. What image would my instrument make of that man who killed because he did not cover up his penis; what possible text would it create in turn to represent this irrationally affecting scenario?

Every family photograph, when put into the literate projector, would be translated into text: a teleplay of an episode of a television show now in syndication. And when every teleplay from any of these shows is put into the projector on reverse, every family photograph will be projected.

My sister and I refuse to interact with the props, which disappoints my mother, who was hoping we could hold something in our hands to represent our connections. We were not reading a newspaper. We read them. We just do not talk about them. Except when someone who never does the word jumble does the goddamn word jumble. Or we look at high school sports track and field results. J. Kenyon jumped 39-5 feet in the triple jump. L. Holwerk ran the 3200 in 10:28.91. Meters and feet. What’s been cropped out of our portrait might be me saying to my father over breakfast “How long is the 3200?” and instead of working out that 400 meters is one lap and then dividing I just let him do it. We’re never as interested in the relays. You can never take the 1,600 relay and divide the time by four to get each person’s split, to see if they’re running faster than you ran fifteen years ago. Someone is always holding shit up. The person waiting for the baton starts to get clinically anxious as everyone else hands off and she’s still waiting.

In the act of having a family portrait taken we are momentarily immune from history, from metric conversions, from sexual preference. We are primarily aware of the camera and how we want to be captured. If the photographs we cling to are candid, consider this: we have a family portrait taken because we are supposed to have it taken because everyone else has them taken and if we do not we will not meet one of the defining characteristics of a family: a group of people who have their picture taken together. This is what we do not see, what we do not understand, what is perfectly present in each family portrait. We never ask ourselves how vulnerable we will become when we look at it in the future, when I watch an ex-lover recoil from the sight of my bad haircut, which made my head resemble the wider base of a Christmas tree, when we see that what’s composite shows at the seams, like how I do not know my mother’s mother’s maiden name; this is when we see that being unable to recognize ourselves does not make us the victors we thought it might.

My mother’s mother died while giving birth to her. My mother has never said she did not know how to be a mother, but I know now how she was worried. How she could understand how to be a mother without ever having had one. But she knows the awkward matriarchal ministrations better than anyone else. But she does not know what a photograph of a mother being a mother looks like, and so she is free to be the mother in our family portrait, not a woman trying to look like one, having just asked me for the third time to clean the cat puke off the stairs.

Photograph 1: John Collier’s “Family of a Portuguese dory fisherman” (circa 1942). From the Library of Congress: LC-USW38-002081-C

Photograph 2: From The Secret Museum of Mankind, published in 1935, with no author, no copyright, no page numbers, no index. “The Cheerless Homestead of the Andine Indian.”