MAPS FOLIO: SMALL PARTS OF A VANISHING words by Joseph P. Wood, with photographs by Sarah Jennings

This is the story of The Tallgrass Prairie National Monument. The story falls squarely on these topographic coordinates. The coordinates predate the Act of Congress, the agent for the monument’s name. The congress is a body and the, definite article, makes it the body’s possession. The story of possession is a story of the definite. The definite coordinates, but in doing so, subjugates. This subjugation, if indeed definite, is a topography of national vanishing. A nation, to be a body, must know its borders. A nation possesses naming and fights its name by knowing. Knowing is a story that acts upon our bodies. It acknowledges no monuments.

Here an eye fronts a singular stalk, a blue opened or closed. The others stalks, be they opened or closed, are blurred, which is to say distorted. Distortion, in this case, exists so the image owner can direct the perceiver to a distilled, controllable grandeur: a singular blue, more blue than the others. The horizon point, a stasis of big sky blue and the even blurrier landline, appropriates distortion differently than the front. The horizon line—or vanishing point, as some painters call it—is a term that has transmuted eras, which means the owner of the eye herself is distorted, as her eye becomes the object of the vanishing point she captures. Moreover, any image these grasses can only capture 20% of the fronted figure. The figure, caring nothing of the I, roots 2/3 below the surface. Likewise, other I’s watch another’s eye blinking, a blue opened and closed. The owner’s optic nerves, which root into the brain, keep the eye in place, and feed it synaptic pulses like rain, are seen only by the coroner when they no longer are useful.

Here exists a collective. To live, the group requires diversity to endure adversity. There are hundreds of others of this collective in the back, but the apparatus to capture the collective can only choose one. To exist is to live sometimes in the front, sometimes in the distance. Fronted we see one sect or see a thousand shoots of maybe six varieties of grass—the individuals. The slant on the left exceeds the image’s border, just as a collective existence exceeds its living iterations. The baby bison are framed out. This does not negate their hooves and mouths. When they bite, the animals both pressurize the collective and are entanglements within it. To sustain collective life—in essence to endure—is a gentle game of diverse collection versus an unintended hoarding. In this sense, mouths are their own small vanishings.

Are we a tiny parting, another small ecosystem of I? Just so panoptic, these slopes and rises, folds of dirt leading on to other folds. The bodies and each body—corporal iterations, mysteries of future intention. It is indisputable they will part. Tiny I in an ecosystem of We, each rooted thing. The front slowly closes toward the center, and the line becomes the center, and the human couple, from this new distance, is outsized by the high left clouds. Another second passes and the human bodies go elsewhere. The grass, the center, the lines, the clouds: an ecosystem of parting, each with their clocks.

We draw a line: the bent figure to the bare vessel of branches. It is hard to say how shadow would shape if the bending figure approached and stood beneath. So many potential angles for this static fleck of long brown hair and of yellow/purple jacket. The line from head to foot gets lost in the grass. From lost, let us line the slight downhill to its convergence with the sharp uphill, where all the browns and green seem to pour down. What shall we name the top? What lies will we tell ourselves today? The grass, in the wind, not shown, runs like a flipbook of infinity. The lost point to the head is actually connected to the limestone and shale only revealed in the hump on the viewer left of the tree. “How do I know you are real?” the bending figure asks the line. The line replies, “follow me.” The figure, face now brought into the sun, says “I can’t go where you go, line.” The line replies, “then you must have faith—to believe what I tell about what you do not know.”

The grass, if we look at the road—an artificial stress—has been exorcised as opposed to trampled. On the left side, up close, the brown tufts stick out, and they are, in this iteration of time and light, stubborn and deep. So that is the story I say. The human forms, each in their inductive progression, say the story differently, and the totality of our differences composes a different story, one closer to knowing. In this sense, what we say is given shape by what is omitted, unintended, an accident of contradiction. I do not believe, if I recall, the parted bodies went to the water. The water, like Arabic, requires no dialectical. Every step and every wind is its own synthesis—an accordion of ripples of wind and bird call and bison lap, which this moment, frozen as object, does not reveal. The figures thus are not parting or joining—if I suggested such a thing, my mind, like this road, is a totality of rocks.

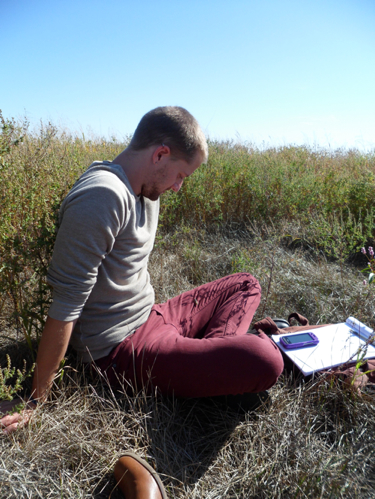

The grass bent under the weight of the body. The figured, robbed of its context, could rise or could disintegrate. Both are forms of movement. And the grass, in its way, would be moved as well, though not of its own accord. The question for the eye is if the foot across the leg is accompanied by blood flow. And that book, a journal or a bible (both we ascribe particular gravitas)? If the body no longer possesses agency, rest is rest in a more disturbing light. The opposite here is snow. And if the body possessed an agency, still clinging to that book, we would, I suspect, deduce rescue is in order. Don’t you see—every cell in the centered body—possibly afloat—or the figures in the road distorted by distance—require rescue. We can be our own rescue; it is a question of pressure. The front is a front because a circle is implied, but chopped off by these borders. If one chops too much, the pressure is prescribed a name: grief.

A collection of congruent directions. Each set of eyes process what each set of eyes process. The purple flowers, which we all have missed, will be given to fire. This is why the hand in the hair, the head turned toward the left (if that is indeed a finite coordinate), the dead man indeed not dead, the hands over what is an apparatus of limited sight take the shape of explorers. It is, indeed, a perplexing job. And since the landscape has been fixed, as in given a name the way every breathing thing is named, we are looking to find ourselves beyond the landscape’s fixing. We are romantics. Fire to the grass is stimulation and control. A birth and a death reside as singularity, a perpetual ledge of karma—who knows what fire kicks out? We know if fire moved toward us, the sky would darken, the smell would give birth to coughing. And if we, terrified of what we cannot know, stayed within our immolation, what within us would be stimulated? This is not about our liking.

Here the shadows darken our particulars. Our collectivity is in our separate grappling. This one scribing, this one flower-leveled. One head up, one head down. The head toward clouds—atmospheric puffs, who over the course of this story, have fractured apart gradually. Over the story, the figures on the road have moved toward abstraction. The water, once a full pond, now is chopped from our sight. The eye and the apparatus have their own motions as well. But their motions, residing within the intuitive, do not inquire how each figure, in its privacy, wishes to be portrayed. Likewise, each stalk of grass, hitherto given no intellection, cannot appropriate its function in this scene. If one believes an ecology enacts the system it is, it’s an enactment devoid of intention. Wander and wonder function as kinesis and locatives. Failure resides in taxonomy.

If human and conscious, we, like babies, stare at the body to understand it is our body. Wave the hands in front of the face. In a matter of months, the infant defines its borders. This is not knowing, for knowing requires an immersion of what composes the hand’s negative space. Let us then speak of spectrums, of lowering one’s self into the grass, of composing the self as a tactile vessel. The leg folded in, the hand nestled between two grasses. A foot suggests another negative space. But so does the grass, thatches of death and life, little roofs that sustain the collective. When we lean upon the roof, we come closer to the roof only if we let the roof supply its story.

The subject, aware of the eye and the apparatus, knows a smile is in order. The power of the eye and of the apparatus lies beyond intention, a form of possession. I can tell you the figure’s gentle orbital lines set off against the ease of the smile—a back and forth of my eye, now writing—imply a nation gone right, the mystery of altruism. The grass, almost level to the smile, if I drew a line, becomes a symbiosis of the face. A kind of grace emerges here, and the clock, as I know it, has stopped. I feel the beard against the wind, neither of which I experience or possess. It is all speculation, but this speculation swirls like the grass thatch dead center past the folded leg. The eye not the apparatus senses this. The eye is rooted in the shooter, not the lens. The shooter’s name, not of her own volition, is Sarah. I cannot say I know her.

It will snow. The light will pale. What falls squarely in the archway will fall disfigured on the bison’s back. Then we pass. I have poured over the artifacts of loved ones, left and leaving. The earth is not meant to like us. With every small vanishing, another birth—or maybe not, and we fight the borderless fight and arrive where the low cloud merges into the sky itself. This is a game of angles. The figure in the picture is cosmic redundancy, a topography of vanishing. There is no bending. That is the story.